Belarus: Freedom and sanctions in a pipeline country. Posted: Canadian Dimension, June 4, 2021.

Western outrage against Belarus flared again on May 23 when a Ryanair flight destined for Lithuania was diverted to Minsk by an alleged bomb threat. Onboard and detained was opposition journalist and activist Roman Protasevich, a key coordinator of the post-election protests in Belarus last year. The country had previously issued a warrant for his arrest in November.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken castigated “this shocking act” and condemned Belarus’s “ongoing harassment and arbitrary detention of journalists.” He said the US stood with the Belarusian people “in their aspirations for a free, democratic, and prosperous future.” Prime Minister Justin Trudeau followed suit.

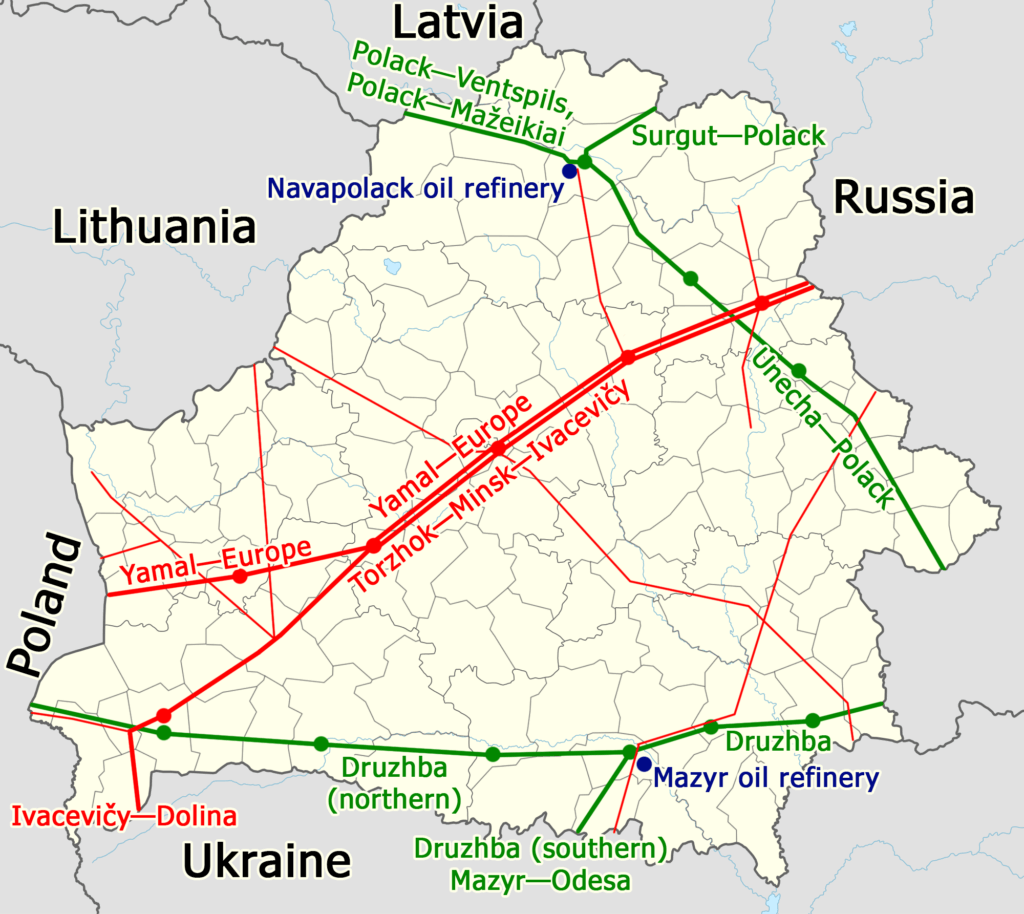

From a Western viewpoint, Belarus is an outlier. Its neighbour Ukraine is a NATO partner, and other adjacent states (with the exception of Russia) are also members of the alliance. What’s more, the landlocked republic is located in a strategic position. As a recent NATO report observed, Belarus “serves as a vital energy export and transit gateway for Russian energy.”

The US sees Russian energy as a security issue for Europe. Russia is the world’s largest exporter of oil and gas, and pipelines and sea routes to market are vital to its economy. A vast pipeline system delivers about one million barrels per day of Russian oil via Belarus to central Europe. Two major pipelines transport Russian gas to Poland and other European countries.

The petroleum sector is crucial to the Belarusian economy, earning about US$1 billion a year in pipeline transit fees. Its two state-owned refineries process Russian crude oil and export petroleum products—the nation’s largest export earner. Belarus also imports Russian oil and gas for its own market.

For a few months in 2020, Belarus imported crude oil from other countries, taking advantage of ultra-low prices during the coronavirus pandemic. They included two cargoes from the United States, after US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo visited Minsk offering “competitive prices.” Facing a hostile West after the August 2020 election, Minsk resumed imports of Russian crude at a renegotiated price.

For the West, President Alexander Lukashenko’s re-election was the last straw. His main rival, Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, refused to concede after widespread accusations of vote-rigging. According to election officials, Lukashenko won 80 percent of the vote while Tikhanovskaya received close to 10 percent. Tikhanovskaya took refuge in Lithuania and received Western support as Belarus’s interim leader. Russia’s foreign minister Sergey Lavrov commented, “No one is making a secret that it is all about geopolitics, about the struggle for the post-Soviet space.”

There is a long history of Western support for the Belarusian opposition. The United States, Canada and other countries have long-standing assistance programs for democratization and human rights within the country. Western sanctions date back to the 2006 presidential election, after which the US, European Union and Canada sanctioned various government officials. They were not endorsed by the United Nations Security Council.

The US also targeted the oil and petrochemicals sector, imposing sanctions on the state-owned enterprise Belneftekhim in 2007 and again in 2011. This is one of Belarus’s largest industrial complexes, accounting for half the nation’s total exports. Washington temporarily suspended sanctions in 2015, when Belarus released six political prisoners and facilitated peace talks in Ukraine.

Upon Lukashenko’s re-election in 2020, Washington imposed sanctions on Belarusian officials held responsible for the crackdown on protesters. Canada, Britain and the European Union followed suit. This April, Washington reimposed its previous sanctions, including those on Belneftekhim.

The US has never targeted the oil and gas pipelines transiting Belarus, which also transit America’s staunch ally Poland. Instead, Washington focused its wrath on the nearly-built Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline from Russia to Germany under the Baltic Sea. On May 19, in a major policy reversal, the Biden administration announced it would not impose new sanctions on European firms participating in Nord Stream 2, recognizing the project is a fait accompli. The US signalled its desire to mend fractured relations with Germany.

The Ryanair incident presented a new opportunity to grandstand on Belarus. EU leaders agreed on May 24 to impose aviation restrictions on Belarus. Their foreign ministers met on May 27 to debate extending sanctions beyond individual Belarusians to encompass key economic sectors such as oil and petrochemicals, potash and finance. No decision was announced after the meeting. The EU has never sanctioned the Belarusian petroleum or potash sectors, both of which state-owned. Belarus is the world’s second largest producer, after Canada, and potash is the country’s second largest export earner.

For the West, the brouhaha over Ryanair and Protasevich conveniently glossed over a much more serious incident four weeks earlier. In April, authorities in Minsk and Moscow announced the arrest of nine Belarusians for plotting a military coup against Lukashenko. While the embattled president claimed Washington was responsible, US authorities denied involvement.

Western actions are pushing Belarus closer to its only friendly neighbour, Russia. Twenty years ago, the two countries agreed to create a Union State of Russia and Belarus, but little was done to implement the treaty. Now, integration is being discussed. Belarus is already a member of the Eurasian Economic Union and other organizations created by Russia and other former Soviet Union states.

Countries imposing sanctions risk cutting off their nose to spite their face. For example, after Lithuania imposed sanctions in 2020, Belarus started exporting petroleum products to Europe through Russian Baltic ports instead of by oil train to the Lithuanian port of Klaipeda. The port lost 30 percent or more of its income. Lithuanian oil trains also took a hit. In addition, Russia and Belarus are planning to export potash and timber through Russian ports.

Expressing solidarity with the US and Europe, Canada has joined in sanctions against Belarus, citing its concern for democracy and human rights. But sanctions that hurt the economy are unlikely to win hearts and minds. On the contrary, they are almost certain to create misery for people in the targeted country. Since sanctions have failed repeatedly to achieve their intended results, what purpose do they really serve?

John Foster is the author of Oil and World Politics: the Real Story of Today’s Conflict Zones (Lorimer Books, 2018).